Where Jacksonville began at Fort Caroline

Story and photos

by Kathleen Walls

Published

6-13-2024

For those who decided Forbes recent

statement tha tJacksonville is the worst place to visit, I beg

to differ. There is so much to see and new things like the USS

Orleck have brought miore visitors to the River City. Jacksonville

has a good hold on

the tourism market. People come to see the art museums, like

Cummer and Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA). They visit

TIAA Bank Field to see the Jaguars play football. They ride

the River Taxi for a Sunset Cruise or over to

see The Museum of Science & History (MOSH) but they often miss

the original Jacksonville. Did you know that had the weather

had been different, Jacksonville might be Florida, and the

United States', oldest city?

; ;

Timucuan Ecological and Historical Preserve

I learned so much aobut Jacksonville's

beginnings when I visited the preserve where Fort Caroline is

located. It's in the northeastern corner of Duval County.

Timucuan Ecological and Historical Preserve

is a

46,000 acre area that protects some of the most environmentally

sensitive marsh and waterfront ecosystem in the state. This

is where the Saint Johns and Nassau rivers,

Jacksonville/Duval County's northern boundary, merge into the

Atlantic Ocean. It's a treasury preserving a tiny bit of North

Florida as it was when the first settlers stepped ashore.

Another treasure is there; the preserve encloses some of

Florida's earliest history.

Jacksonville's Early History

Had the winds of fortune blown differently (literally),

Jacksonville would be America's oldest city. About a year

before Pedro Menendez established St. Augustine, French

Huguenots settled here. They called their settlement

Fort

Caroline in honor of the French King Charles IX.

When the Spanish Catholics came to settle Florida, conflict

was inevitable. Both men were charged with claiming Florida

for their respective countries. On September 5th, the two men

made first contact, Menendez on his San Pelayo

and Ribault on his flagship Trinity. A few

shots were fired and the French slipped away.

Menendez returned to San Augustine. The two colonies

were just about 38 miles south apart. Realizing their

vulnerability, Menendez sent his big galleons that could not

cross the shallow harbor bar, back to Santo Domingo on

September 10th.

Ribault pursued the departing Spanish vessels. A sudden

Florida hurricane blew into the French ships and wrecked them.

Menendez, realizing Ribault could not return to Fort Caroline

in time to prevent an attack, marched his men overland to Fort

Caroline. Menendez captured it without any losses. Of the 240

Frenchmen, the Spanish killed 132, sparing only a handful of

Catholic Frenchmen. A few escaped but the victory was

overwhelming.

|

| Today a replica of a later Spanish fort marks the

massacre site. It's a few miles south of St. Augustine

Beach off A1A |

Meanwhile, two separate groups of shipwrecked Frenchmen were

walking through woods and swampland back towards Fort

Caroline. When Menendez learned of this, he marched south with

about 50 to 70 men. They found the first group of 126 drenched

despairing Frenchmen near the south end of Anastasia Island.

There, at a small inlet, he encountered the first contingent.

With little choice, they surrendered to him. Menendez ordered

all killed with the exception of 15 Catholics. On October

12th, Ribault and remaining 350 Frenchmen reached the inlet.

About half of the Frenchmen surrendered and the rest decided

to take their chances in the woods rather than trust Menendez.

All but 16 prisoners were rounded up and slaughtered in the

already bloody marsh. Today, that inlet is called Matanzas,

Spanish for slaughter.

Because of an ill wind, France forever lost her chance in

Florida. There would not be another town here until 1822, the

year after Spain ceded Florida to the United States. It was

originally known as known as Cowford because this was where

the settler drove their cattle across the St. Johns River.

Then in 1822, it was mapped as a town and named Jacksonville

after Andrew Jackson, Florida Territory's provisional

governor.

Fort Caroline National Memorial

Fort Caroline National Memorial memorializes the short-lived

French presence in sixteenth century Florida. The site hosts

the visitor center and a small museum that tells the history

of Fort Caroline's French Huguenot settlers, the early

Timuquan Native Americans influence, and the ecological

factors of this land. It's open 7 days a week is from 9 am to

4:45 pm.

The displays inside tell of the settling of Jacksonville and

have many actual artifacts. When the French settlers arrived,

the Timucuans helped the settlers acclimate to this new wild

land.

The Timucuans knew how to use nature's resources; shells for

tools, fiber and baskets were created from saw palmetto, logs

were hollowed to make dugouts. Because of the huge water

resources, fish and shellfish were a main source of food. The

French landed named the huge river The River of May. Today we

call it the Saint Johns River. Nearby Mayport memorializes

that earlier name.

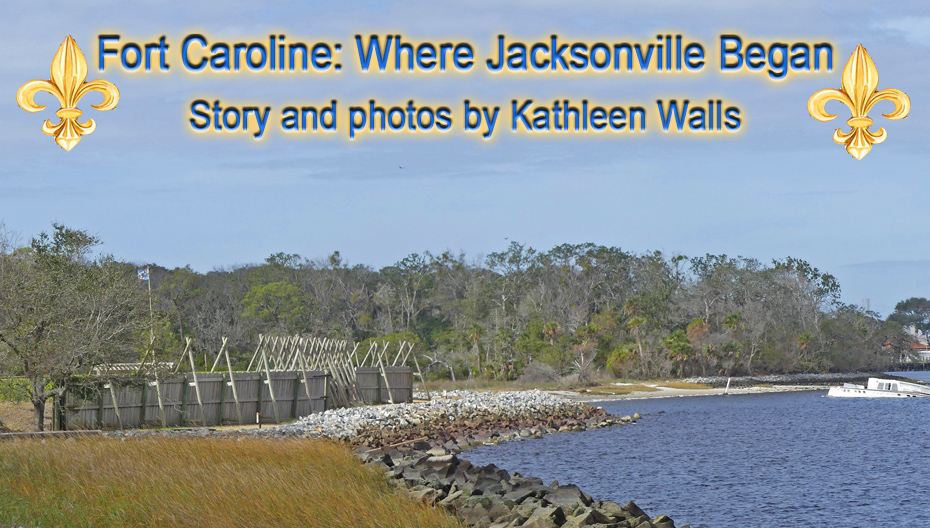

The reconstructed Fort Caroline shows how the settlers built a

village here. There's a replica of an oven. Ovens were built

outside the fort to prevent the fire from igniting gunpowder.

There's a replica of a Timucuan home and shelter with a

Timucuan dugout You enter the fort through gates with a French

coat of arms. You'll see the cannon replicas that were

supposed to protect the fort. This fort replica is about one

third the size of the original fort.

Just a short distance away, Ribault Monument stands

overlooking the St. Johns River. It replicates the stone

column Ribault erected, bearing the coats of arms of the

French king and claiming Florida for France, in 1562. The

native Timucuans often decorated the marker and revered it.

Next time you visit Jacksonville, go see where it all started.

We'd love your comments!

Public Disclosure

Please Read

FTC has a law

requiring web sites to let their readers know if any of the

stories are "sponsored" or compensated. We also are to

let readers know if any of our links are ads. Most are not.

They are just a way to direct you to more information

about the article where the link is placed. We have several ads

on our pages. They are clearly marked as ads. I think

readers are smart enough to know an ad when they see one but to

obey the letter of the law, I am putting this statement here to

make sure everyone understands. American Roads and Global

Highways may contain affiliate links or ads. Further, as their

bios show, most of the feature writers are professional travel

writers. As such we are frequently invited on press trips, also

called fam trips. On these trips most of our lodging, dining,

admissions fees and often plane fare are covered by the city or

firm hosting the trip. It is an opportunity to visit places we

might not otherwise be able to visit. However, no one tells us

what to write about those places. All opinions are 100% those

of the author of that feature column.

|